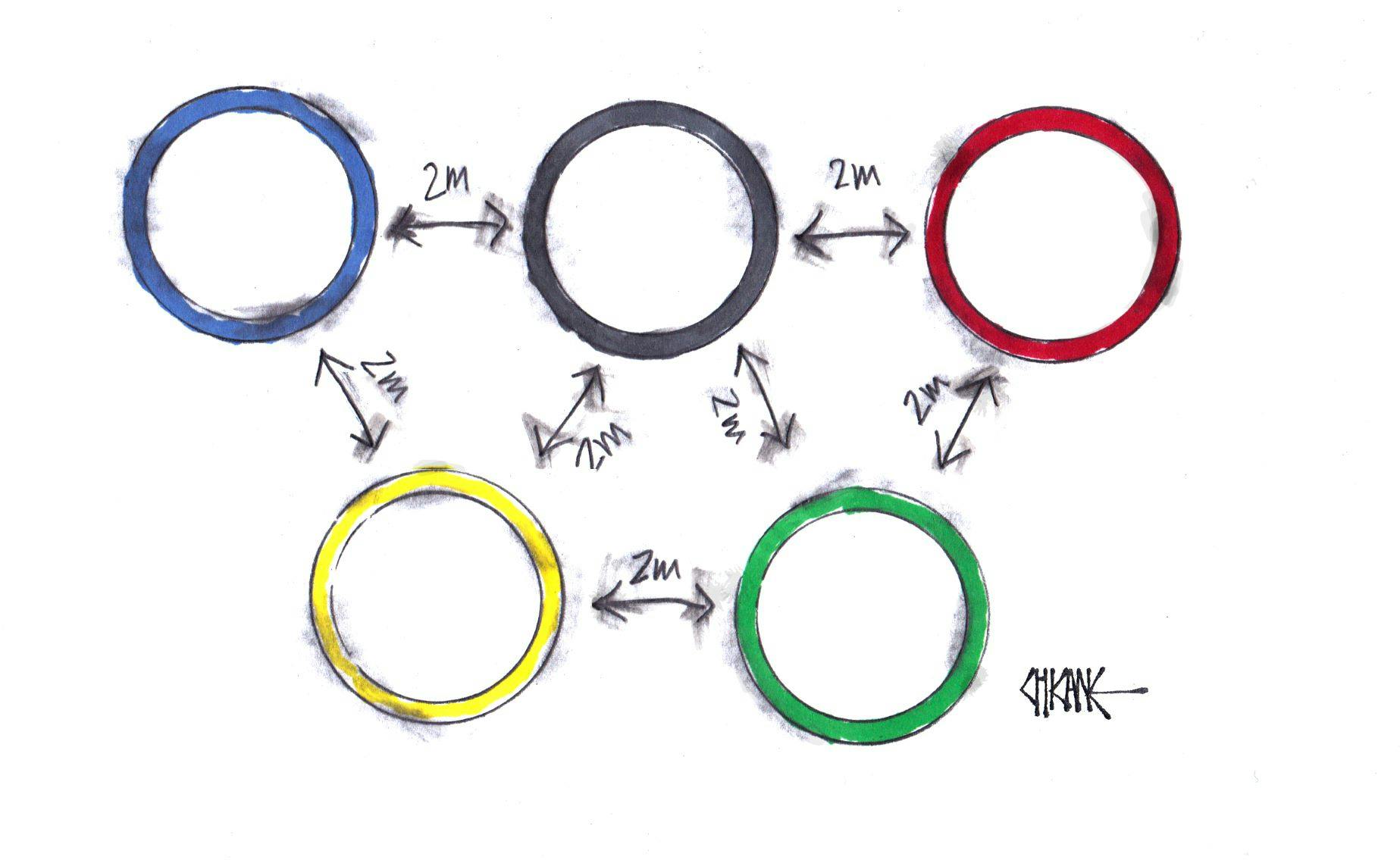

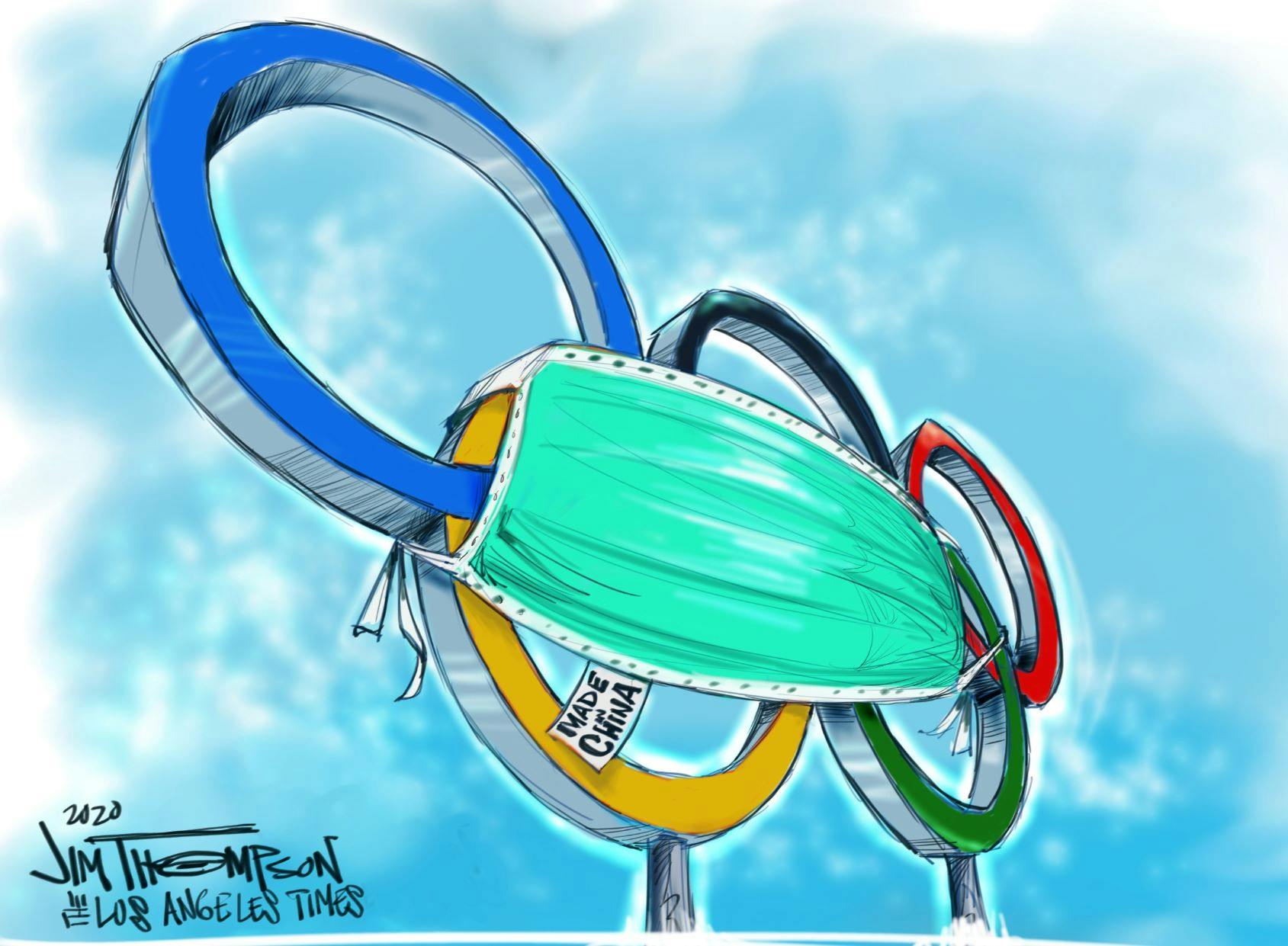

The 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games were the 20th Olympic Games (Summer and Winter) that I have been privileged to attend. Clearly, they were not normal Games. Many, especially the world’s media, questioned the wisdom of holding the Games during a global pandemic. The traditional pre-Games critics went into overdrive, lambasting the IOC for its insensitivity in imposing its sporting spectacular on a reluctant local public.

In the lead up to the Opening Ceremony, Japan’s finance minister, Tara Aso described the Games as ‘cursed’, recalling the jinxed pattern that seemed to repeat itself every 40 years: from the cancellation of Tokyo’s first hosting of the Olympics in 1940, to the crippling Cold War boycotts of Moscow 1980, to 2020 and the first ever postponement of the Games.

When, between 2013 and 2015, 187 human corpses were excavated from an Edo period (1603-1868) cemetery within the construction site for Tokyo’s new Olympic stadium, inevitably, an old Japanese urban legend was revived: the curse of Prince Tokugawa Iesato, one of the last feudal lords of old Japan. It was Iesato who had been president of the Organising Committee of the hapless 1940 Tokyo Games.

A slow vaccine roll-out, combined with a weak, to near non-existent communications programme from the Japanese government, created the perfect environment for the Olympic agenda to be highjacked by the political opposition and other groups with an eye on scoring points in the lead up to the upcoming general election.

With stories of how the Games could become a super-spreader event, the Japanese media turned ‘populist’ and fueled an already nervous and at times xenophobic public, who are at the best of times, averse to risk and surprises. Foreigners arriving in Japan were portrayed as carrying the Ebola virus or worse, and their presence risked wiping out the Japanese race.

In 1964, Japan had seized the opportunity to demonstrate its transformation from a militarist aggressor to a fully-fledged member of the community of responsible nations. Six decades on, as the world’s third-largest economy, Japan’s technology, popular culture and cuisine did not need another Games to prove their international credentials to the rest of the world.

In the weeks and months leading up to the postponed Opening Ceremony, public support for the Games crashed, with some polls reporting levels of opposition up to 80 per cent. Against that backdrop, under the pretext that public gatherings would allow Covid to spiral out of control, Prime Minister Suga was forced to take the decision to ban all spectators from the venues.

Yet, when I arrived in Japan in the days before the Games opened, the local TV stations were full of images of local baseball and sumo wrestling with stadia packed with spectators. It slowly became apparent that the decision to ban spectators from the Games was perhaps more about political expediency than Covid health protocols.

So as not to create any aura of celebration, the all-powerful Tokyo Governor, Yuriko Koike, demanded that all forms of Olympic pageantry and flags be removed from the city. The few Olympic officials who were able to enter Japan as part of the strategic delivery of the Games, were banned from attending the Opening Ceremony. Indeed, everything was done at a political level to make the Olympic guests feel they were not really welcome.

Yet, once the Games started, the volunteers showed just how much I and other guests were welcome. I cannot recall a more welcoming or hospitable group of volunteers at any previous Olympic Games. Then, as soon as the Japanese team started winning medals, the Japanese public became passionately supportive of the Games, setting all-time record TV viewing ratings. However, the biggest tragedy of all was that the Japanese people were not allowed to attend their own Games. It was truly heart-breaking to travel to venues and watch families along the side of the road waving to the official buses and cars, trying to capture their special Olympic moment.

The ‘Cursed Olympics’ were rapidly being transformed into the ‘Miracle Games’. It was not only a miracle that they were happening, but a miracle that the IOC had succeeded in bringing 205 nations to Japan in the middle of a pandemic.

The Tokyo Olympic Games began to take on an important role, not simply a homage to the Olympic motto of ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’. After being isolated from each other and locked up in their homes for months on end with little to celebrate, the Games became a tangible illustration of ‘bringing the world together’. Such was the power and symbolism of uniting the world, the IOC decided to add ‘together’ to the Olympic motto: ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger, Together’.

The Financial Times captured the mood in its closing editorial: “These Olympics have been a balm for souls battered by the pandemic.”

Broadcasting

Tokyo probably saw more changes in broadcasting, than in any other area, with the introduction of Covid protocols fast-tracking several key areas of production.

Original plans to ‘test’ cloud technology as a platform for transmitting the broadcast signal and data around the world, suddenly had to be fast-tracked, as broadcasters struggled to get their staff and production crews to Japan. Some production teams came close to being halved, and studios were set up back home rather than in Tokyo. Thankfully, cloud technology provided a seamless link between the host city and the rest of the world.

The reduction in technical broadcast personnel from levels that had been exploding in recent years due to the dramatic increase in number of hours of production, now creates interesting opportunities to significantly downsize on the ground operations and potentially deliver major cost savings. Smaller international broadcast centres, reduced transportation and accommodation requirements, will all help to reduce the overall operational scope and complexity of the Games.

Yiannis Exarchos, the head of Olympic Broadcasting Services has described the partnership with cloud partner, Alibaba as, “Perhaps the biggest technological change in the broadcasting industry for more than half a century, since the introduction of the satellite”, which, incidentally, also happened in Tokyo, at the 1964 Games.

As a result of the dramatically increased production hours, viewership in many countries exploded, setting new records, as people had more choice to watch more sport – and on their own terms.

Not all broadcast ratings were up, and some countries did see reductions in their audiences, whether due to time zone challenges, lack of on-the-ground atmosphere, or poor promotional build up. But a word of caution here; as the media continues to focus on just the network ratings, which is no longer a valid measurement as to how an event is being consumed, it ignores the broader reach across other platforms. The ratings industry is living in a prehistoric world and future audience reports must present a fuller picture.

Digital consumption saw massive increases, but the Games ultimately remain a big screen, family/friend viewing experience. The IOC needs to go back and examine in detail, not just the ratings of each market, but what drove the viewing consumption. It needs real qualitative research to explain why some markets, like the UK and Australia, enjoyed great success, while others, like Spain, did not.

Another Covid-driven initiative that has the potential to impact and enhance the Olympic brand and overall broadcast presentation, was the introduction of screens for athletes to connect directly with their family and friends back home immediately after their competition. With everyone prevented from going to the stadium, the IOC decided to bring athlete families to the stadium digitally, with closed circuit screens set up just before the media mixed zone as the athletes left the stadium.

Some of the most emotional broadcast moments at any Games have often been the athlete connecting with his/her family immediately after their competition. Few families have the resources to travel to the Games and this new initiative allows every athlete to connect back home. The IOC’s broadcast arm, Olympic Broadcast Services (OBS) working with local broadcasters back in the home market of each athlete, was able to take the viewer back to the village and join in the celebrations, creating a truly global village broadcast. It was powerful and something that the IOC should take forward to all future Games.

Sponsorship

Tokyo 2020 was on target to be the most successful Olympic marketing programme ever. The local partner programme had set records, with over $3bn (€2.6bn) generated (nearly three-times more than London or Rio). Aided by the occasional nudge from Japanese advertising giant Dentsu, all of the great and the good of Japanese industry queued up to support the Games. Dentsu was the Organising Committee’s marketing agent, as well as the agent for much of Japanese industry. Dentsu delivered on the dollars and dodged all claims of conflict of interest.

The stage had been set for Japanese industry to present its new technologies, just as it had amazed the world nearly six decades earlier with Tokyo 1964, and the introduction of electronic timing and satellite transmissions. This time it was to be robotics and new forms of digital engagement.

Then, with the decision to postpone the Games, everything was put on hold, except for Dentsu’s bizarre attempts to hit all the sponsors for an additional year of fees, as they argued that the sponsors were getting an extra year to activate. That deserved a gold medal in twisted logic.

In the end, the sponsors never got to activate anything. Ticketing, hospitality and showcasing programmes were all cancelled. Then the decision was taken to pull all advertising, as it was argued, especially by some politicians who wanted to tone down any sense of celebration, that it was not appropriate to communicate anything celebratory about the Games in the context of the gloom and misery of a pandemic.

As a consequence, the biggest single legacy from Tokyo will be a complete rethink on sponsor contracts, with an increased focus on insurance cover, rebates and the delivery of rights.

The pandemic has also made companies far more focused on CSR and social support programmes, and here the Olympic Movement is perfectly placed to respond, with multiple platforms that sponsors can take advantage of, from the Paralympics to the refugee team, and educational programmes.

Licensing

With no international visitors in Tokyo, or local spectators, licensing was hit hard like the sponsor programmes. But the licensing programme, also managed by Dentsu, was never going to succeed, as it was set up to fail from the outset.

The Olympic Games enjoy some of the most diverse, innovative and creative designs, as each host country seeks to present its design credentials. For some bizarre reason, the Tokyo licensing managers never sought to include the tremendous depth of design and culture of Japan into the Olympic licensing programme. Instead, they stuck to the faithful and boring protocol of ‘logo slapping’. As a result, there was little of any innovation or proper design introduced into the Tokyo programme. It was a missed opportunity.

Hopefully in the future, French (Paris 2024) and Italian (Milan-Cortina d’Ampezzo 2026) style, and Californian (Los Angeles 2028) innovation will not repeat the same mistake by missing the great opportunity to create a real connection to the fan base and enhance the brand of the host nation. The IOC also needs to raise its game and give clear guidance and leadership, and not just focus on the legal/technical approvals about whether the pantone colours of the rings are correct.

Budgeting and finance

The media and the activists had a field day when it came to the cost and budget for the event, presenting the Tokyo Olympic Games as the most expensive ever. I am not sure they were.

The Japanese have always been exceedingly creative with their Olympic budgeting protocols, finding ways to sneak anything they can into the Olympic budgets. I recall in 1998 before the Nagano Olympic Winter Games, challenging the financial director of the Organising Committee about why venue construction costs were so high. One line item for an indoor skating venue, had costs of over $200m for landscaping. When challenged on how this was possible, I was told: “Olympics great project, central government pays for all Olympic related costs…and landscaping included new 18-hole golf course.” Of course, golf was not yet an Olympic sport, and certainly not one for the Winter Olympics.

For the future, the IOC has to take a much harder line with host countries about what actually gets listed within the Olympic budget. The Games have often served as a long-term catalyst for capital development, from Barcelona 1992 to London 2012 – but these costs really should not be listed as Olympic budgets, as they only serve to distort the whole financing debate.

The IOC has already moved to introduce much more flexibility into the hosting process, recognising that each host has different requirements and objectives. The Tokyo Games will hopefully be the last where the finances get so misrepresented and distorted.

Legacy

Tokyo brought many other issues to the forefront and will leave a long-term legacy for the sports movement, whether it be Simone Biles withdrawing due to the ‘twisties’ and the ensuing debate about athlete mental health, or the need to rein in the increasing trends of cyber bullying on social media platforms.

Tokyo became a memorable and successful Olympic Games, but for very different reasons than originally envisaged. With an atmosphere drained of the traditional pomp and full of anxiety, the attention turned fully onto the athletes and their Olympic journey, one of survival and resilience. Theirs was a journey not that different from the journey of the Olympic Movement itself: its ability to survive over the past 120 years, no matter what challenges have been thrown at it.

Michael Payne has recently authored a new book: Toon In! – an insider’s unofficial and entirely unsanctioned history of the Olympic Games. To find out more go to: www.olympiccartoon.com