Heather O’Keeffe is a FIFA Master alumna 2021 and current revenue strategy and planning trainee at FIFA. The following article shines a light on one of the group projects undertaken by O’Keeffe and some of her classmates from the 2021 FIFA Master edition.

Heather O’Keeffe is a FIFA Master alumna 2021 and current revenue strategy and planning trainee at FIFA. The following article shines a light on one of the group projects undertaken by O’Keeffe and some of her classmates from the 2021 FIFA Master edition.

After years of hard work, hustle, and pioneering spirit, women’s football has broken into mainstream sports media. Seemingly every week a new spectatorship record is broken at a women’s football match. However, this success comes with a big caveat: records are being broken and women’s football is making headlines in Europe, North America and Australia. For being widely understood as the world’s game, women’s football is hardly close to being accepted, much less respected or celebrated, in many parts of the world.

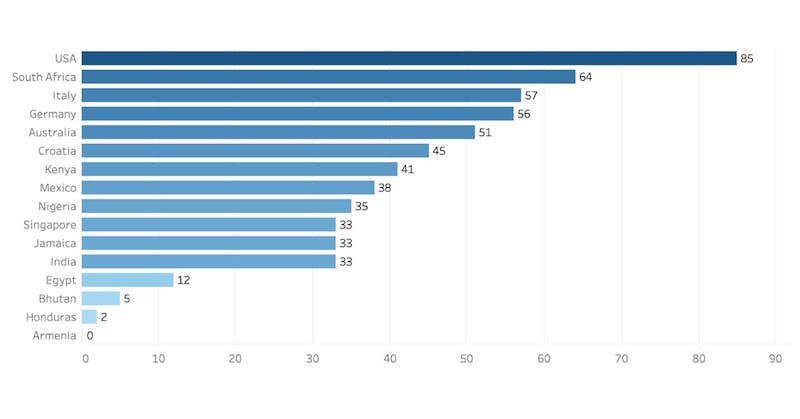

One glaring indicator of this disparity in the acceptance of women’s football around the globe is the number of matches played by senior women’s national teams. During the last FIFA Women’s World Cup cycle (2016-2019), the USA played 85 matches, Germany played 56 matches, and Nigeria competed in 35 matches, while the Egyptian women’s national team played just 12 matches, Honduras played two matches and Armenia did not play a single match.

Total number of women’s football matches (2016 – 2019)

How do we ensure women’s football grows around the world? And young girls in Egypt, Honduras and Armenia can cheer on their women’s national teams just like young girls in the USA, Germany and Nigeria?

This is exactly what my colleagues (Thomas Grimm, Lorenzo Mazzone, Diana Yonah) and I set out to understand through our thesis during our FIFA Masters studies. We wanted to understand the key reasons for the existing gap between national team strength in women’s football through a holistic methodology. We tested four hypotheses against 44 key performance indicators (KPIs) across five categories: economic, geographic, socio-cultural, political and sporting. By taking a broad, holistic approach, we analysed the implications of broader societal context on the scheduling of women’s senior national matches. This research was conducted on a sample of 16 out of 211 FIFA member associations.

The results of the research paint a very clear picture of the state of women’s football and the obstacles it faces in becoming mainstream in various cultures and countries around the world.

First, we found a close relationship between economic indicators (e.g. GDP/capita) and the number of matches scheduled for a women’s national team. This can be intuitively understood: nations with disposable income can afford to direct public and private funding to support elite athletes, whereas in financially insecure nations that funding is more urgently needed to provide basic services.

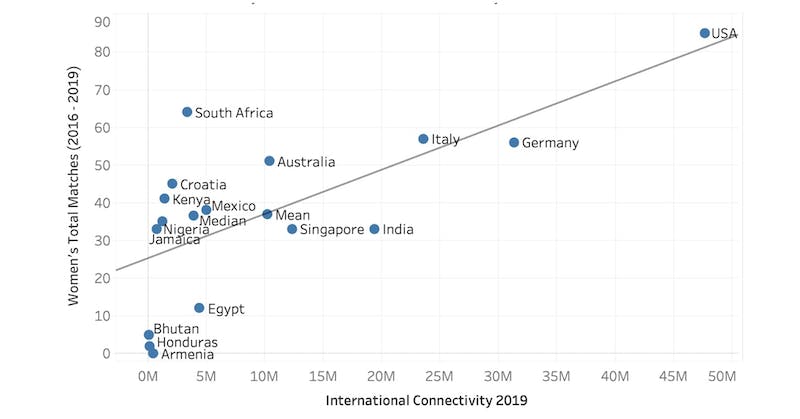

Geographic isolation also proved to be a statistical obstacle to the scheduling of women’s football matches. Countries with a lower International Air Connectivity score have limited access to global air transport, and thus it is more difficult and more expensive to organise travel for senior women’s football matches. For example, there are fewer flight options for the Bhutanese women’s national team to travel for tournaments and friendlies than the Italian women’s national team.

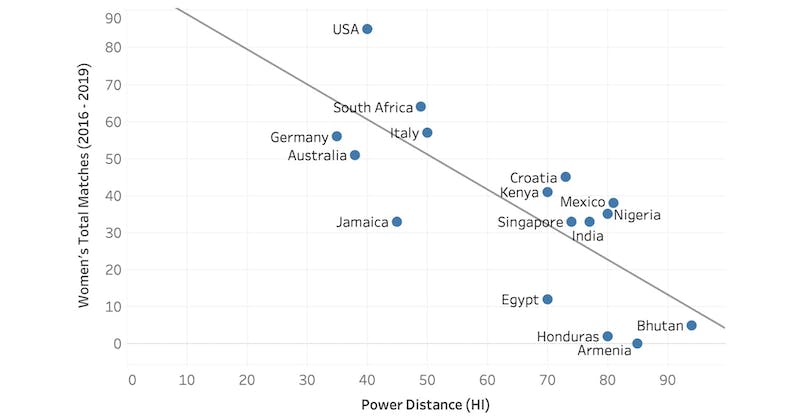

In an analysis of socio-cultural obstacles, two clear indicators emerged. Power Distance, a social indicator which quantifies the role and acceptance of hierarchy in a society, had a statistically significant relationship with the scheduling of women’s football matches. Our analysis found that in countries where vertical hierarchies are prevalent, such Egypt, Honduras, Bhutan and Armenia, fewer matches were played than in countries that have a flatter social hierarchy such as Australia or South Africa.

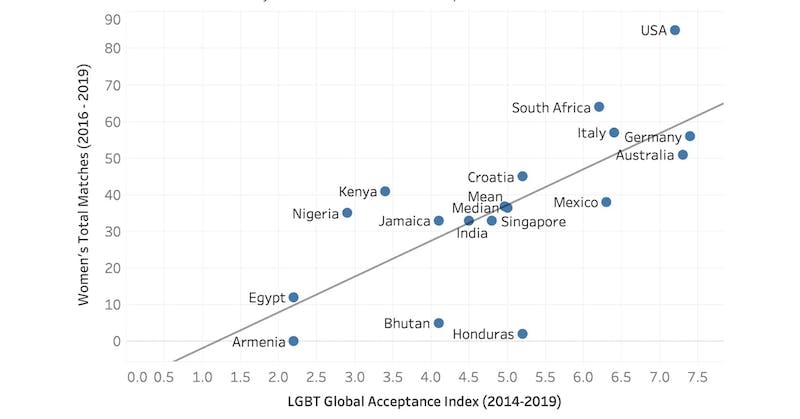

Another noteworthy socio-cultural indicator was the level of LGBT acceptance in a society. Countries and societies which had a higher overall level of LGBT acceptance had more active women’s national teams. This finding was supplemented through interviews with women’s football administrators who described interacting with parents who didn’t want their daughters to play football as they were fearful football would “turn their daughter gay”. This harmful stereotype can position football as a non-desirable activity for girls and young women.

This research clearly showed that a variety of factors impact the acceptance and promotion of women’s football. The most startling finding was that the indicators that were statistically significant obstacles for scheduling women’s football matches were not statistically significant for the scheduling of men’s national team matches in the same country. A low GDP/capita, limited ability to travel internationally, or a rigid hierarchy were all surmountable obstacles in the face of men’s national team programmes. This finding suggests that a lack of willingness to invest in women’s football is perhaps the most significant hurdle to the scheduling of senior women’s national team matches (although a much harder obstacle to quantify). In the end, of the 16 countries analysed, women’s national teams played, on average, 30 per cent less than their male counterparts.

As women’s football continues to grow and develop, special attention must be paid to the broader societal and cultural contexts in which women’s national teams operate. Landmark solutions in one nation are not plug and play solutions in countries with their own unique cultural and financial contexts. Organisations and administrators driving the exceptional growth of women’s football should carry out similar holistic analysis of the societal context to properly identify solutions which will allow women’s football to truly prosper around the world. If we want girls and women to succeed on the pitch, it is imperative to consider the extenuating circumstances impacting women’s football development that extend far beyond the touchline.

This article is part of the 2022 SportBusiness Postgraduate Rankings. To browse the entire report and view the overall tables, click here.